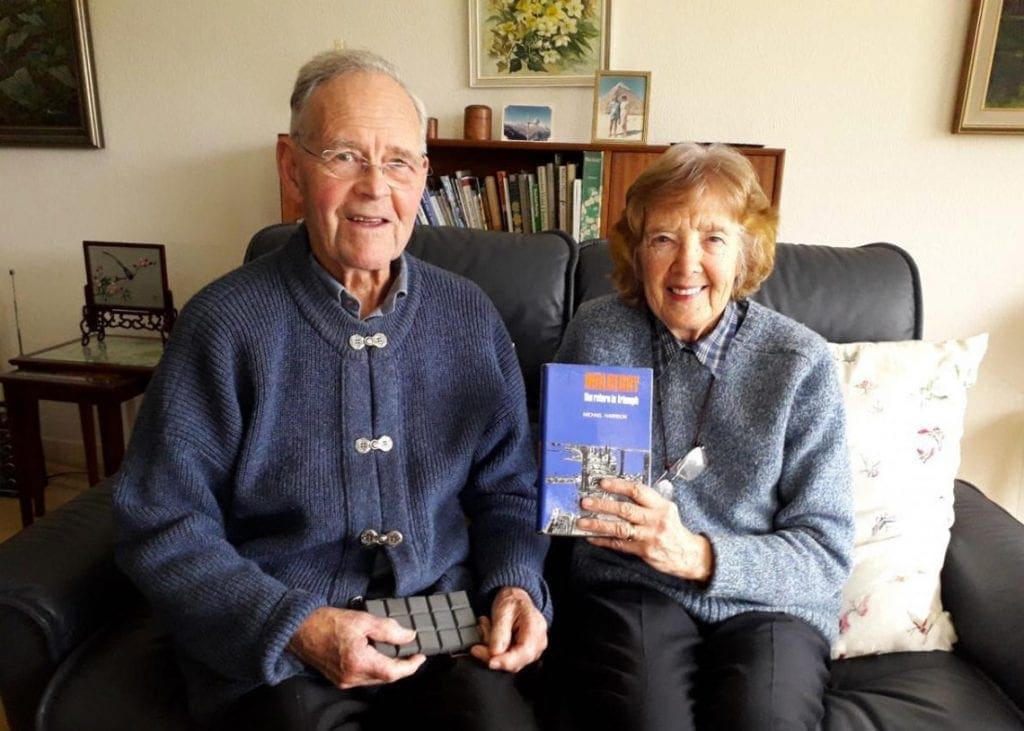

A Keswick man has told how his uncle worked alongside Sir Winston Churchill masterminding the secretly-planned D-Day landings to help secure victory in the second world war.

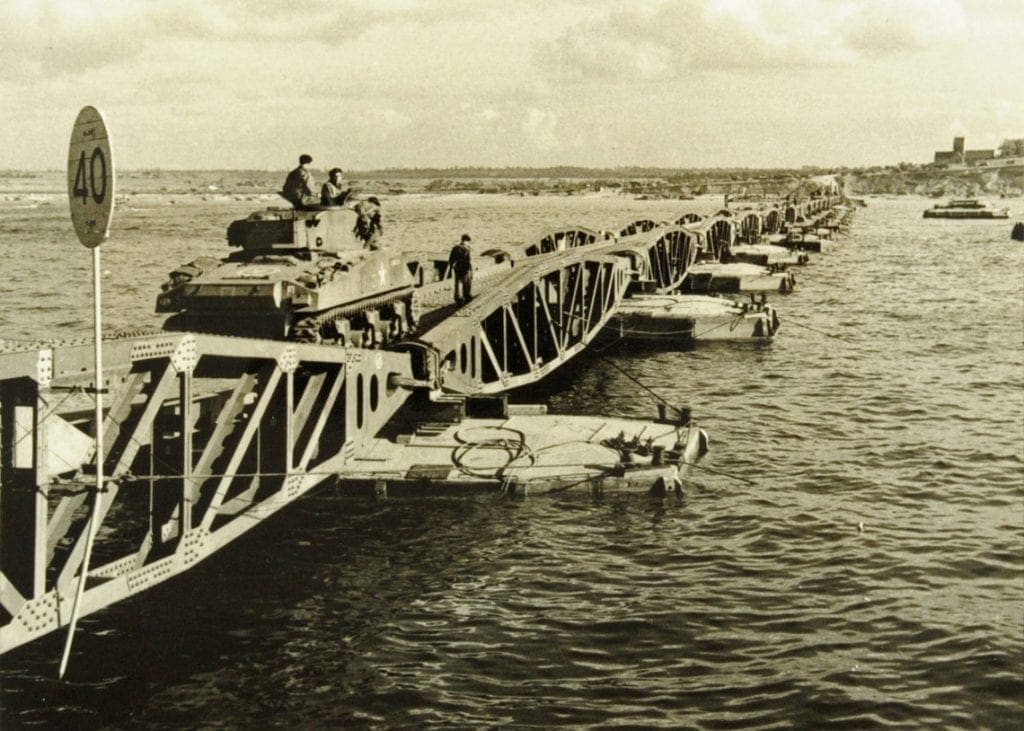

Canon Brian Selvey, 87, is the nephew of Colonel Vassal Charles Steer-Webster, who produced the giant flexible floating concrete mats – known as chocolate blocks because of their distinctive shape – which enabled Allied troops to successfully complete the Normandy landings at artificial Mulberry harbours in 1944.

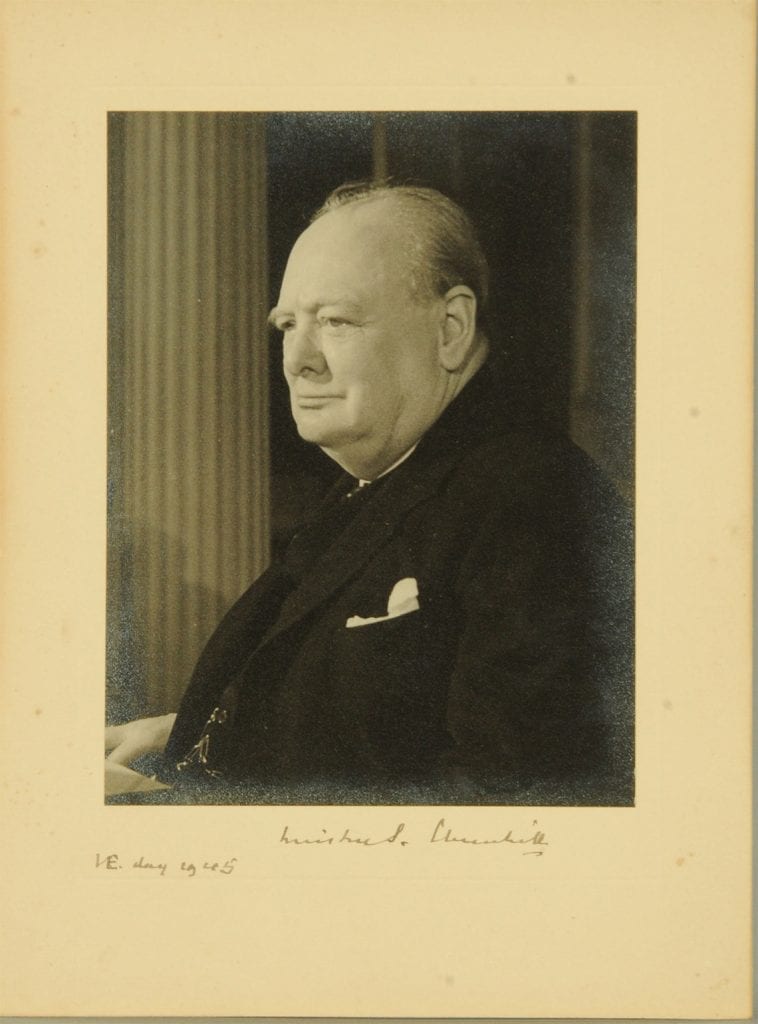

Colonel Steer-Webster’s ingenious engineering feat paved the way for VE Day the following year when he was awarded an OBE. He died in 1970 and when his wife too passed away, as the couple did not have children, his unique collection of military items, including rare secret documents and a signed photo of Churchill, was passed on to Canon Selvey and his wife Gillian.

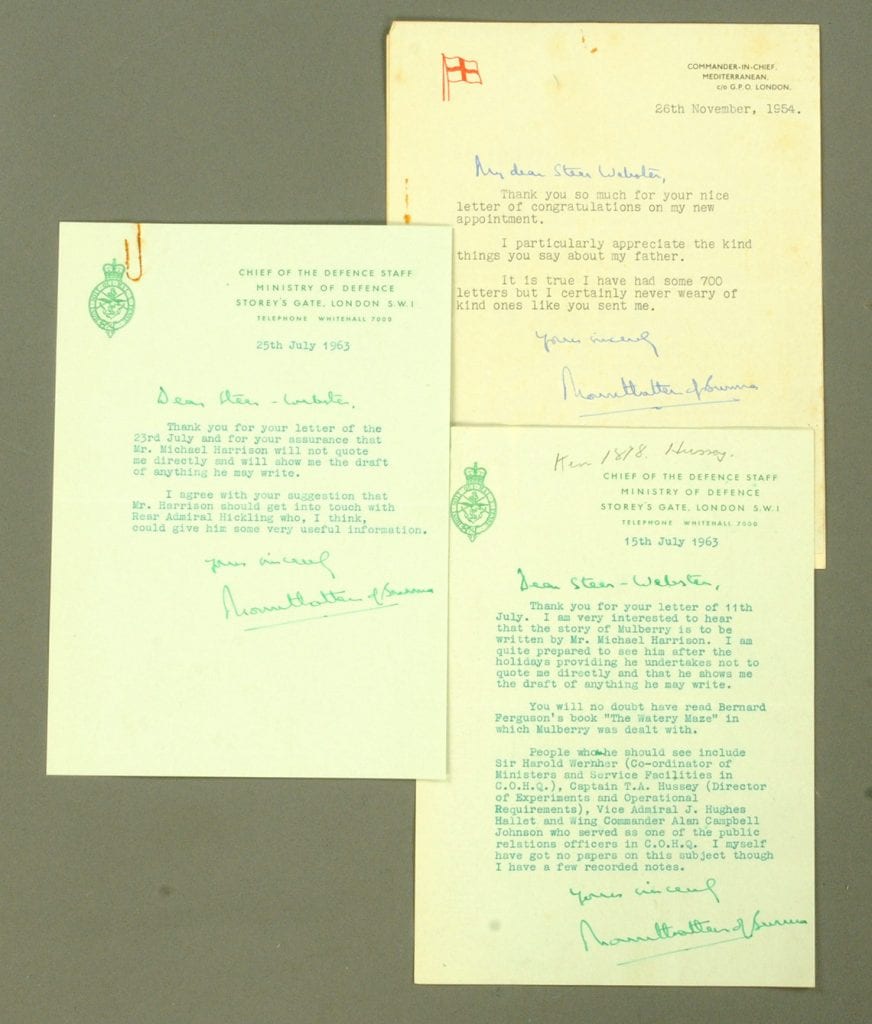

The couple, who moved to Keswick in 1998, are also childless so they sold the colonel’s military collection at Mitchell’s auction in Cockermouth in March, the Royal Engineers Museum paying £28,000 for it via a telephone bid. The personal archive also included a bullet removed from Colonel Steer-Webster when he was in action as a private during the first world war.

Canon Selvey, who used to visit his uncle in hospital, had insisted the collection was not split up into individual lots but was kept together. Focusing on the link between his uncle and the current VE75 commemorations, he said: “It was only because of the Mulberry harbour that we won the war and Churchill was able to announce VE Day. They realised they were never going to win the war by invading ports that already existed. He (Col Steer-Webster) had the idea that if you could make concrete blocks hollow, then they would float.

“He had a job convincing Churchill this would work. It was in 1935 when serving in India that he solved the problem of concrete causeways crossing river beds that always broke up when the rivers came into full flow. He connected strips of concrete by steel rods, making a flexible mat.”

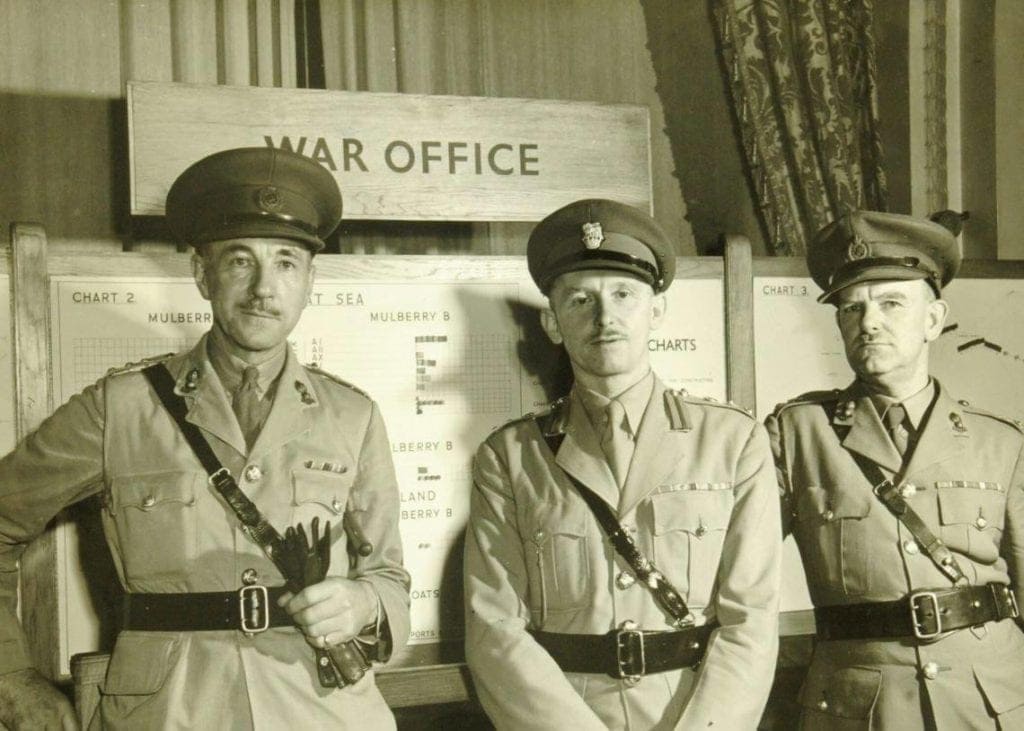

Working in the British government’s experimental engineering office, the colonel, who came from Derby, had led the design and construction of the famous floating Mulberry Harbours which were towed across the English Channel towards the French shore in sections to land troops, vehicles and supplies in the battle for Normandy. This work kept him in almost daily contact with the prime minister in the run-up to D-Day, accompanying him on trips to the USA and Canada.

His archive includes personal correspondence from Churchill, Eisenhower and Mountbatten along with medals, models, engineering designs, documents and over 150 photographs as well as personal items from the First World War including dog tags. One document is the actual minute sent to the colonel by Churchill which gave the go-ahead for Mulberry.