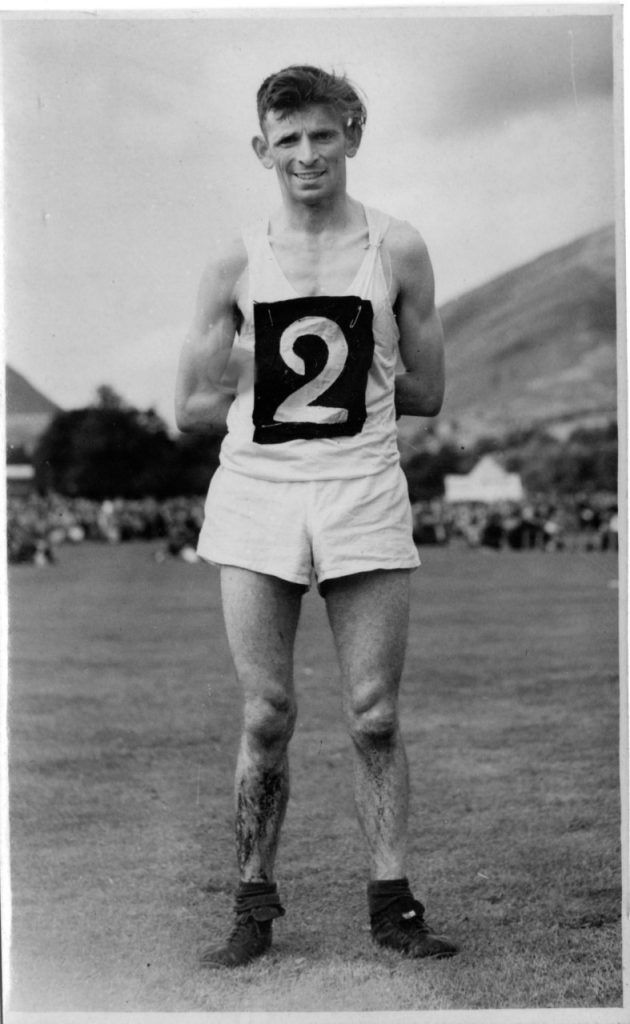

Lakeland fell running legend Bill Teasdale, of Caldbeck, has died at the age of 98.

And with his passing the curtain is finally drawn on what can be regarded as a golden era of Cumbrian sporting history, a time when more than 10,000 and upwards would enthusiastically attend local sports meetings such as those at Grasmere, Ambleside and, formerly, Keswick, writes Keith Richardson.

Bill was a genuine sporting hero and it was appropriate that when Teasdale ran into the arena to win at Grasmere sports, the band struck up the tune See the Conquering Hero Comes.

The same rousing melody is to be played when his coffin enters the Eden Valley Crematorium, Temple Sowerby, at a humanist service on Monday, 23rd January at 2pm.

In his day, Bill was as close as a 1950s local character might ever come to real celebrity. Nowadays sporting superstars are two a penny, but in Teasdale’s heyday you had to be something truly special to warrant that sort of adulation. Not for nothing was he known as “The King of the Fells”.

He was certainly special in his field, but he was down to earth and hefted to the fells in and around Caldbeck. He was of true, Cumbrian farming stock and while small in stature he was in some respects larger than life, a fascinating character with a wide range of interests. And he remained physically fit and active until his mid-90s.

Born and raised at Todcrofts Farm, Caldbeck, on 29th October, 1924, he was rooted in the countryside “back o’ Skidda” and was one of eight children born to his parents, George and Annie.

Bill is the last of the eight – having been predeceased by Joe, John, Annie, Margaret, Jean, Grace and Hilda. Today he is survived by seven nieces and nephews and their families.

Bill attended the village school, then followed in his dad’s footsteps and went to work on the farm at Todcrofts and also at other farms in the area. He later spread his career wings and became an engineer, specialising in working on BBC installations and masts and his work, at times, took him to other locations in the UK where his skills were required.

He never married, preferring an independent lifestyle as he became a fell runner of note and a man with a wide range of other interests, the latter mainly related to the land, farming, history, wildlife and geology. As he grew older Bill became a man of immense local knowledge.

He could talk for hours on a fantastic range of subjects and once he got started was difficult to stop, his monologue moving swiftly and seamlessly from one topic, and occasionally eras, to the next with hardly a breath.

He did not move far in terms of where he chose to live and, after Todcrofts, it was not until the late 60s that he moved house for the first and last time – and then it was only a couple of hundred yards up the road to Bushby House. He lived there – tending his vegetable garden – next door to a niece, Barbara (who would provide him with meals left on top of the hedge between the houses in the back garden).

A couple of years ago ill health meant he had no option but to move into retirement homes, the first in Caldbeck – until it closed – and then, latterly, one in Maryport where he died last Friday.

While his primary sporting pursuit was fell running, Bill was often called upon to lay the scented trail for local hound trails and he was also a keen shooter, with rabbit and other game often finding its way into his pot. He was in every respect a country lad.

His achievements in running are well documented and to provide some key elements of his amazing record, he won the Grasmere senior guides race 11 times – the last when he was 42 – and won at Keswick on 12 occasions, 10 times in a row. His success came at a time when officialdom in the amateur ranks frowned on the so-called professionalism of those who took part in the Lakeland games such as Grasmere, Ambleside and Keswick where winners and runners-up received modest cash prizes handed out in brown paper envelopes. And it is perhaps a pity he never had the opportunity to run on a bigger stage.

Bill’s trainer for many years was Bobby Thirwall, a window cleaner from Keswick, and one of Bobby’s key tasks, before a sports meeting was to place Bill’s false teeth in a little tin box where they were kept safe until Bill had run – and usually won — his race.

Bill was so far ahead in the fell races he won that lower placed competitors might ask on finally getting back from the fell to the sports field: “Has Bill gan yam yit?”

He was full of laughter, had a mischievous glint in his eye, and did not mind if the humour was at his own expense.

One day in his sitting room at Bushby House he told me of the time he decided to buy a new car. When he returned home with it he drove straight into his old tin-sheeting garage just across the road from the house, only to find that, once inside the garage, he could not open his car door.

The new car was wider than the old one and was, quite literally, jammed into the garage. Bill had no option but to reverse out and then cut a door in the side of the garage, directly in line with the driver’s side door. “I had to knock a wol in the wall to git oot and the tin was harder than ah thowt,” he told me in his unmistakeable Cumbrian twang.

On that occasion, and after a fascinating hour or three talking to Bill about shepherding, running, the old times and modern times – he was a formidable critic – I left Bill Teasdale as he wandered into his back garden, looking for signs of an emerging crop of new potatoes or heads of rhubarb.

I always appreciated the description that one writer gave of Bill Teasdale MBE and who likened him – in his white running vest and shorts – to a little white handkerchief fluttering down the fell on his rapid, daredevil descent, leaving everyone and everything else in his wake.

He was a smashing little fella Bill Teasdale and by hell could he run.